A pediatric case in which organ donation was precluded by the legal obligation to perform a forensic autopsy

Mai Miyaji1, Atsushi Kawaguchi1, Naoki Shimizu2.

1Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, St. Marianna University, School of Medicine, Kanagawa, Japan; 2Pediatrics, St. Marianna University, School of Medicine, Kanagawa, Japan

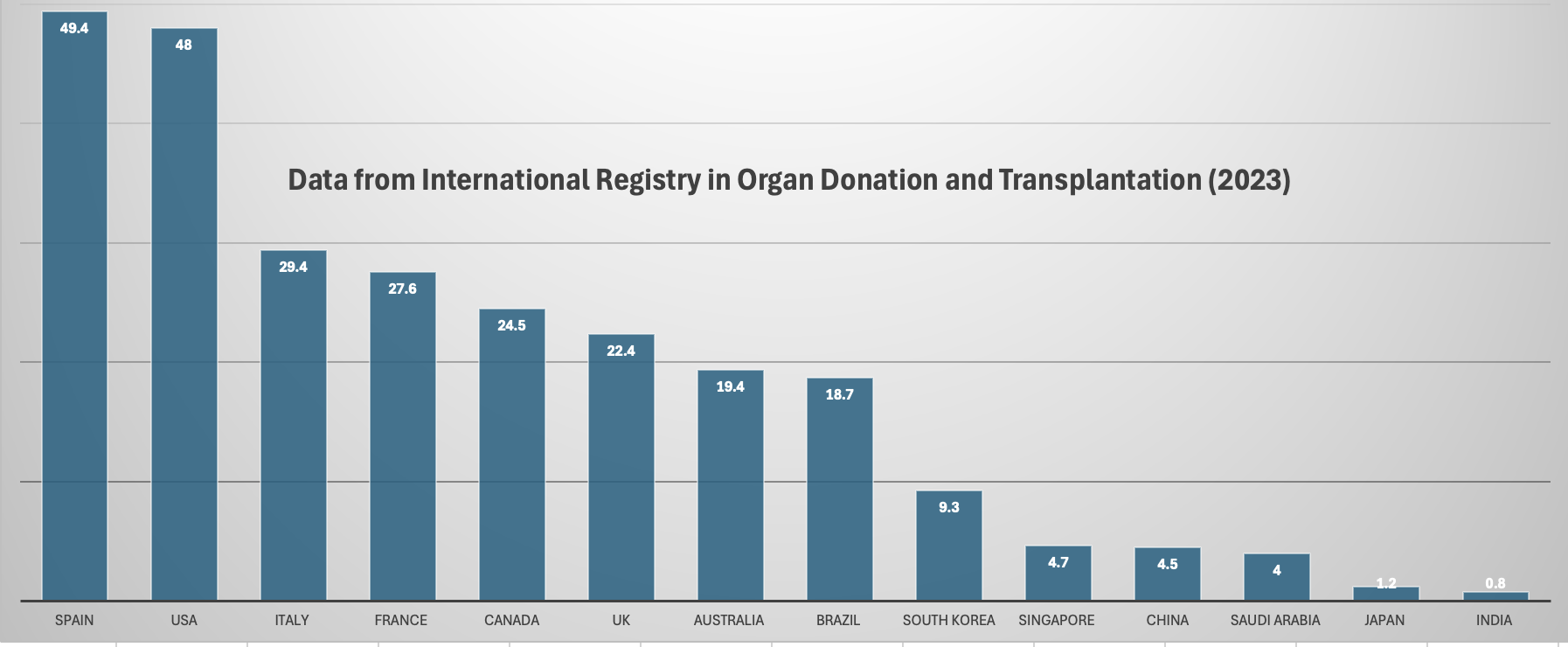

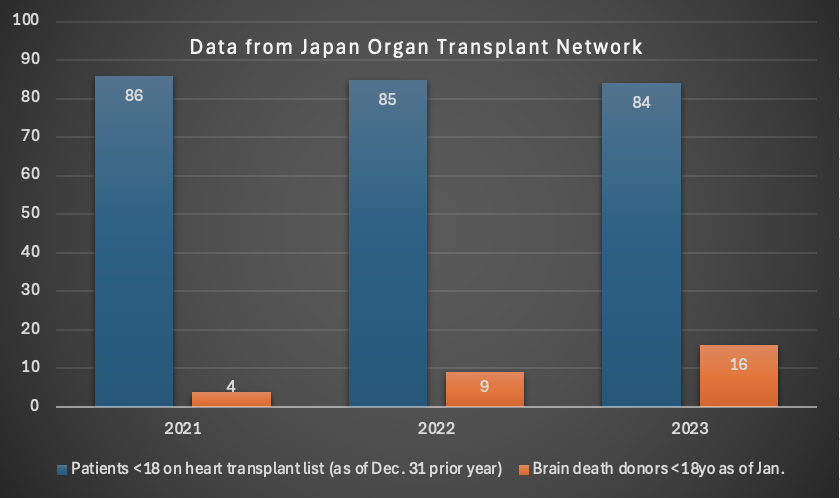

Introduction: In 2010, Japan's organ transplant law was amended to allow donation based on family consent, as well as organ donation under brain death from children, resulting in an increasing number of donations. However, the number of organ donations is limited, and a substantial gap exists between demand and supply.

Case: A previously healthy 1-year-old male aspirated spherical cheese under his grandfather’s supervision at the grandfather’s home, resulting in cardiac arrest upon hospital arrival. After the return of spontaneous circulation, he ended up in brain death. The in-hospital abuse prevention committee judged abuse to be unlikely. The option of organ donation was presented to the parents, and they wished to donate organs under brain death. After consultation with the transplant coordination team, a local police team was contacted. Due to the police decision to proceed with a forensic autopsy, the legal brain death exam was not performed, and the patient was discharged as cardiac death on day 13th.

Discussion: Obstacles to pediatric brain death organ donation in Japan

1. Views of brain death

Brain death is not widely accepted as human death in Japan. The Organ Transplant Law of 1997 was the first to officially equate brain death with legal death in Japan, but only in the context of organ donation. Familial consent is required for brain death declaration, which can create challenges for physicians determining brain death, and there's a preference for continuing life support until cardiovascular death.

2. Doctor’s hesitancy to present the option of donating organs

3. Child abuse exclusion requirement

The guideline on the operation of the law states that "if a child suspected of being abused has died, organ removal shall not be performed”.

4. Non-standardized criteria for forensic autopsy

In cases of death from external causes, the decision to conduct a forensic autopsy is made at the discretion of the police, without input from medical professionals. There are regional disparities in police criteria for ordering autopsies, as well as in the distribution of forensic pathologists conducting judicial autopsies across prefectures. Once an autopsy is ordered, it is customary to prohibit even partial procurement of organs deemed non-contributory to the cause of death. This practice contrasts with approaches in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, where partial organ procurement and forensic autopsy may proceed concurrently. Further investigation using national transplant data is warranted to assess the regional disparities.

Conclusion: There are multiple obstacles to promoting pediatric organ transplant in Japan. While it is important for pediatricians not to overlook abuse or homicide, the investigation of the cause of death and organ donation should be conducted concurrently, not in a binary fashion.

[1] Brain death

[2] Medical Examiner

[3] Forensic autopsy

[4] Pediatric organ donation